Fall 2019

4

"Places We Come From":

A Chat with Justin St. Germain

Chris Liek, Class of 2020

“Places We Come From”:

A Chat with Justin St. Germain

Chris Liek

Class of 2020

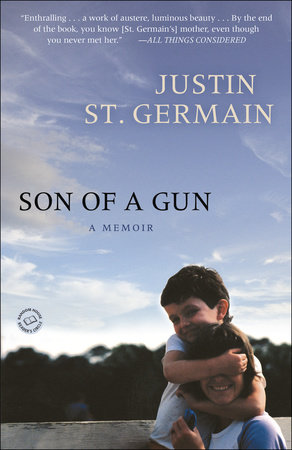

Justin St. Germain is a new faculty member of the Rainier Writing Workshop. He is the author of the memoir Son of a Gun, which won the Barnes & Noble Discover Award, was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, and was named a best book of the year by Amazon, Publishers Weekly, Salon, and Library Journal, among others. His writing has recently appeared in New England Review, Tin House, DIAGRAM, and the Pushcart Prize anthology.

Anyone who was at the 2018 residency will remember Justin’s wonderful morning talk on scope, and his reading from his work-in-progress that kept each of us on the edge of our seats, our breaths held. As I’m sure any mentees that has had the chance to work with Justin will agree, it’s a great honor to have him join the faculty at RWW. This fall, I had the opportunity to ask a few questions of Justin, shared below.

Chris Liek: Parts of your memoir take place in Tombstone, Arizona, a place with already so much history and attention. Can you talk a little about the idea of place in writing, and how Tombstone as a place focused the scope of your writing when working on Son of a Gun?

Justin St. Germain: Place is sort of a natural departure point for me, both the physical landscape and metaphorical or mythical ones. That might be because I grew up in Tombstone, which is in a beautiful part of the world—the high Sonoran desert is one of my favorite landscapes—but also one that’s been the scene of so much violence. It’s not just the gunfight at the OK Corral: the area also saw some of the most brutal fighting of the so-called Indian Wars, and was along the path of Coronado’s bloody expedition into the Southwest. So, it seemed important to acknowledge some of the place’s history, and the way Tombstone conceives of itself as a town built on violence, in the course of writing about a specific act of violence that happened much later.

CL: What are your thoughts about MFA programs? More specifically, can you speak to how a low-residency program, like RWW, fits into those thoughts? What do you find effective in a program like this? What does mentoring mean to you?

JSG: This is the fifth MFA program I’ve taught in, and I went to one before that, so I’ve seen a lot of different versions of the MFA. I think MFAs are valuable, and believe writing can be taught, like any other art or skill. But each program is different, sometimes significantly so—two-year versus three-year, residential vs. low-res—so I really don’t think there are a lot of things you can say about MFAs as a whole. (Unfortunately, that doesn’t stop people from making categorical criticisms of them, most of which are wrongheaded.)

RWW has been my first experience with a low-res model, and I like a lot of things about it. One is that it allows people who can’t necessarily pick up their lives and move across the country for a residential program to get an MFA. That feels more inclusive than the residential model, and allows for a more diverse cohort in terms of life experience and backgrounds. Another is the quality and commitment of the students and faculty. But probably my favorite thing about RWW is the sense of community, which struck me the first day of my first residency: people here know and care about each other in a way that feels unique.

CL: Although nonfiction has been around for a long time, earliest in the form of essays, it hasn’t been until recently that it’s become a major third with fiction and poetry. How do you see the future of nonfiction continuing to push the limit?

JSG: It’s funny you ask that question, because one of the things I’ve been learning in the course of researching my current project is that nonfiction was really the first American genre of writing. (Although, of course, the indigenous oral tradition predates it by millennia.) The first printed books to come out of the colonies were mostly nonfiction, and from the very beginning they had a dubious relationship to factual truth. In that sense, some of the modern controversies over truth in nonfiction writing seem silly, with their ahistorical and often fundamentalist notions about what is and isn’t “true.” I don’t believe it’s possible to write an objectively true account of anything, and wouldn’t particularly want to try, so I certainly hope the genre continues to push the limits of what truth can mean.

"I don’t believe it’s possible to write an objectively true account of anything, and wouldn’t particularly want to try, so I certainly hope the genre continues to push the limits of what truth can mean."

CL: Many writers tend to cross genres at some point. As a nonfiction writer, do you ever find yourself interested in a fiction idea, or poetry? How, in your opinion, can they all blend together from time to time?

JSG: I got my MFA in fiction, so I’m a defector. A lot of nonfiction writers are, especially those who got MFAs before there were many with a nonfiction focus. I think nonfiction, especially, lends itself to writers schooled in other genres: many of the skills of poetry and fiction (not to mention journalism and critical writing) translate well to CNF, and a lot of the best nonfiction writers also work in other genres. I still write fiction, sometimes—I’ve been plugging away at a novel for years—but I think of myself as a nonfiction writer, these days. For me, stumbling into nonfiction was a revelation: I just think there’s so much vibrant, interesting work being done in the genre right now, especially in the essay form.

CL: What are you currently working on?

JSG: Besides the aforementioned novel, which is perpetually on the back burner, I’m working on essays. My main writing project, which I don’t want to say too much about for fear of cursing it, is a research-based, book-length historical essay about gun violence.

Chris Liek (2020) is a third year student in the Rainier Writing Workshop. He writes fiction and poetry and lives in central Pennsylvania with his partner and their son.