Fall 2019

3

“Be Interested in People”:

An Interview

with Renee Simms

Nathaniel Youmans (2020), Contributing Writer

“Be Interested in People”:

An Interview with Renee Simms

Nathaniel Youmans

Contributing Writer

Class of 2020

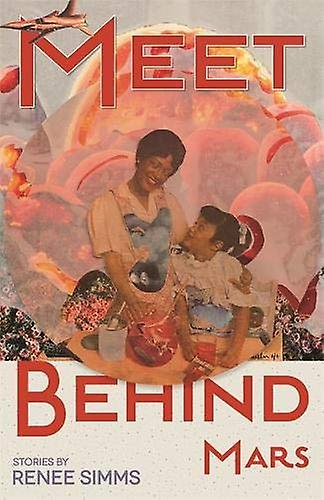

Earlier this year, the Rainier Writing Workshop welcomed four new writers and educators to the faculty, including Renee Simms, author of the short story collection Meet Behind Mars. Renee is an associate professor of African American Studies and contributing faculty to English Studies at the University of Puget Sound. Renee received her B.A. in Literature from the University of Michigan, a J.D. from Wayne State University Law School, and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Arizona State University. She was a 2018 National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellow, a 2018 Bread Loaf fiction fellow, and has received support from Kimbilio Fiction, Ragdale, Vermont Studio Center, and PEN America. Her writing appears in Callaloo, The Oxford American, Ecotone, Literary Hub, Southwest Review, North American Review, The Rumpus, Salon, and elsewhere.

After the summer residency, during which Renee gave a riveting morning lecture about M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, I had the pleasure of asking Renee some questions about teaching and craft. It is my pleasure to share our conversation here.

Nathaniel Youmans: I understand that you were a lawyer before being a professor. Can you describe what led you to depart from practicing law and moving toward writing and teaching? How did your previous career with language translate to your current one?

Renee Simms: I took a lot of literature courses in college as part of my independent concentration, so language and literature have always been passions for me. I thought that law would be a good profession for someone who liked to read and write. I quickly discovered that the writing and reading are very different. In the end, I missed literary language and the careful crafting of words and big ideas like you get in a Baldwin essay or a Morrison novel. It was a tough decision to leave law because a lot of people were invested in my career. But I knew I wanted to write, and when you have writing as a compulsion you will figure out a way to do the work. As it turns out, writing fiction/nonfiction, teaching, and litigation have some things in common. You need to be able to tell a cogent story to an audience. You need to be a good listener. You need to be interested in people: how they speak and what they are saying, not only with words but with their shoulders or eyes or silence. The skills that you need to create fictional characters are the same skills you need to understand what a student needs or how to persuade a jury.

NY: In your morning talk about M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, you led the residency through exercises grappling with the broken, fragmented legal records of the Zong massacre. I really enjoyed doing this calculated linguistic archeology, despite, or maybe because of, the difficulty in establishing or recovering a clear narrative throughout the historical record. Can you talk about how documentary research informs and challenges your writing life, especially when dealing with unresolved historical traumas?

RS: That’s such a great question. I believe that imagination is useful in dealing with unresolved historical traumas. And there are a couple reasons why imagination might be necessary and even helpful in such cases. First, as Elizabeth Alexander, Saidiya Hartman and others have said, imagination can help us understand gaps in the historical record. In the case of the Zong massacre, there are many gaps. We don’t have the names or personal backgrounds of the people who were killed. We don’t have a record of how they felt right before they were thrown overboard the slave ship. But we can imagine these things that we don’t know, given what we do know.

Second, imagination traffics in feeling, which is different than data and facts. We know that Margaret Garner killed her daughter to avoid having her enslaved, but what Beloved does, as a novel based on the event, is make us feel the enormity of that decision. The spectral presence of the dead daughter in that novel is richer than the facts of the case. When Beloved finally comes out of the house at the end of the story and stands on the porch naked, “thunderblack” and pregnant, the reader is blown away by the power of that image. Can you think of a better illustration of the reckoning between the living and spirit world when a mother kills a child to avoid a cruel institution?

"Can you think of a better illustration of the reckoning between the living and spirit world when a mother kills a child to avoid a cruel institution?"

NY: Can you describe a particularly influential mentor that you have had, either in the course of pursuing your J.D. at Wayne State University or your MFA at Arizona, or both? How did they influence your pedagogical style?

RS: My colleagues at Puget Sound in African American Studies have been the best mentors I’ve ever had when it comes to pedagogy. Like PLU, Puget Sound is a liberal arts college, and excellence in teaching is its priority. From my colleagues I’ve learned how to pay attention to each student and all students simultaneously. I’ve learned how to be myself in the classroom. I’ve learned that less is more. I’ve learned how to democratize a classroom and how to quietly close the escape routes that students try to take when the material becomes challenging.

In creative writing workshops that I’ve taken, David Haynes, who teaches at Warren Wilson and is a founder of Kimbilio, has been influential. David gives great advice for workshopping novel excerpts, and he’s also good at teaching close readings of fiction and explaining how to structure a novel. I still think Junot Diaz was an important mentor at VONA, where he introduced many writers to critical race theory so that they were better readers of the way that race, power, and privilege operate in fictional stories.

I’ve also been greatly influenced by Alberto Ríos and Melissa Pritchard, who were mentors at ASU when I studied there. I learned from both of them how to be an effective mentor, how to champion your students and encourage them. I often think of the way they championed and continue to champion me. Enthusiasm and encouragement mean a lot to students when they’re learning and engaging new ideas, new genres.

NY: What projects are you working on right now?

RS: I’m working on a novel that has challenged me in good ways. I enjoy these characters so much that I’m a bit reluctant to let them go. It’s taken a while to understand them and to figure out the structure of the novel, but I’m close to having a final draft. I can’t wait to share it. It’s a story about intergenerational legacies, cruelty, and love.