Fall 2019

2

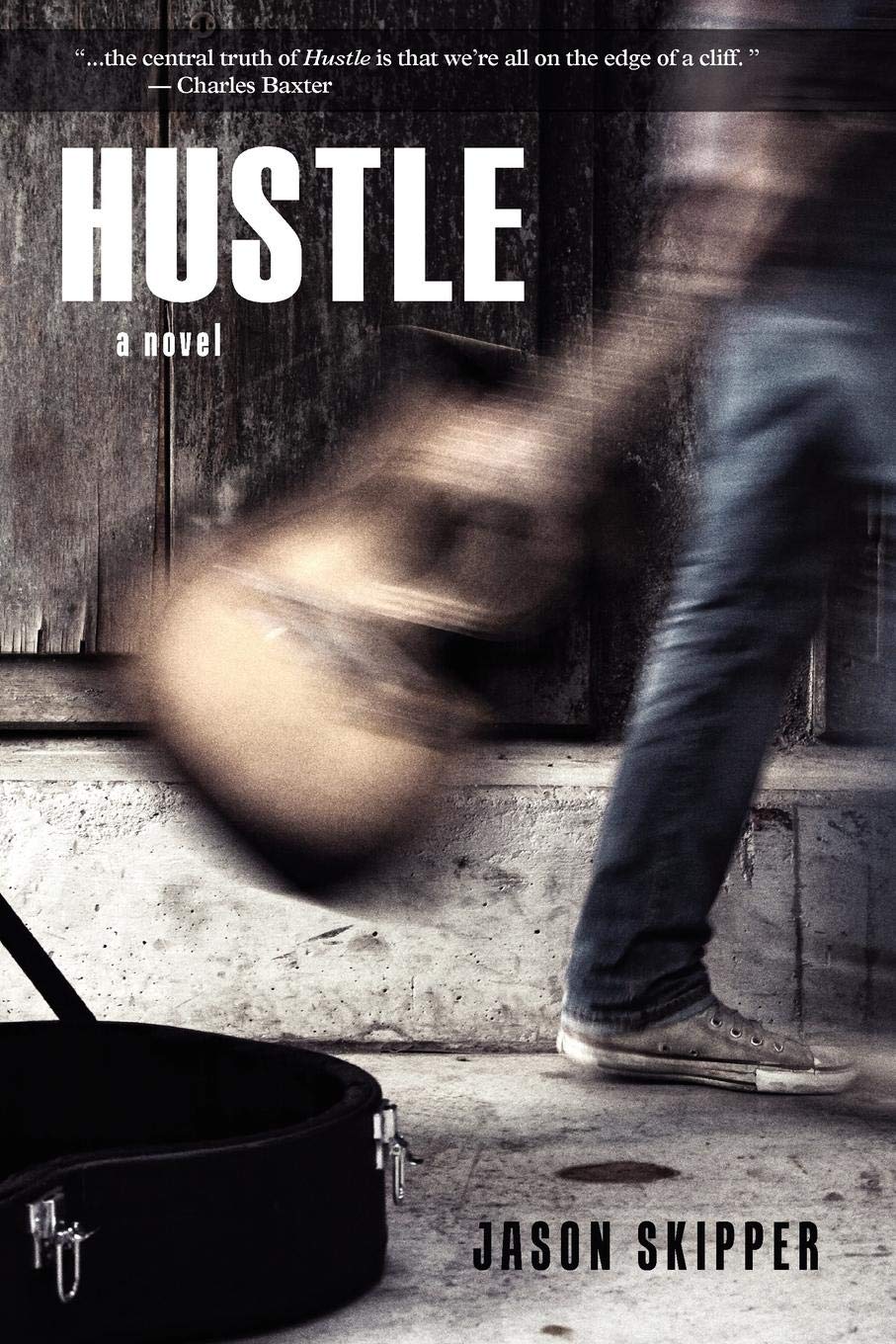

Learning to Let Go

Jason Skipper, Faculty

Learning to Let Go

Jason Skipper

Faculty

The first story I wrote that would later appear in my novel Hustle was about a fifteen-year-old kid named Chris whose alcoholic father has burdened him with the responsibility of running his seafood business alone, set on the day a Health Department Inspector reviews their run-down store. Though Chris is equipped with excuses to protect the business in these situations, he stays quiet throughout the inspection, knowing that if she shuts down the business he’ll be relieved of this responsibility. I based this story on a similar experience I had at sixteen years old while running my dad’s run-down seafood business, when a Health Inspector came and I, equipped with excuses, froze up until finally she told me to lock the doors. After writing this story, I went on to write others about Chris, pulling from personal experiences to shape his struggles to become a musician in order to escape his father’s trappings, not knowing that I was inadvertently trapping him in myself.

As I wrote these early drafts, Chris and I shared many characteristics. We had similar interests, fears, and hopes. In addition, Chris’s first guitar was as crummy as mine. The main difference is my interests shifted from playing music to skateboarding, while Chris’s interests stayed the course. At one point while working on these stories, I knew I’d need to write one in which he finally gets a new instrument, and I decided it only fair I give him a Fender Telecaster, the guitar I would have wanted and what I thought he should have.

". . . I went on to write others about Chris, pulling from personal experiences to shape his struggles to become a musician in order to escape his father’s trappings, not knowing that I was inadvertently trapping him in myself."

In that story, Chris is thirteen and selling shrimp from a van on the side of the road for his father, scrimping his earnings for a Telecaster he saw at a pawn shop near his house. He gets paid a quarter per pound he sells, and that summer he works harder and more frequently than summers before. He does so well his father grows convinced Chris can take over a van himself and work most weekends after school starts, much to Chris’s dismay. I wrote the story in grad school, and nothing up to that one quite compared. It was a time in my life when all of the reading and writing began to click. I finished the piece, revised it, and sent it off with hopes for publication. When it came back rejected, I revised again, though mostly local edits, because I felt I’d made all the global changes it needed. Still, it felt unsettled, and I sensed something wasn’t right. And since sensing may as well be knowing in the drafting process, I knew the story wasn’t quite finished. I had a slight notion what the problem with the story might be. But it was small—simply an object in the story I always got hung up on—so small I couldn’t see how changing it could make a significant ripple. This happened again and again for another two years.

Then one night, I opened up this story on my computer and read through it again to get my bearings on it before I started making more changes. As I read, once again, I got hung up on the image of Chris playing guitar, either on the edge of his bed or on stage in front of an audience, and in that image he wasn’t playing a Telecaster, like it read on the page. He was, like always, playing a Gibson SG (think: Angus Young of AC/DC), a guitar I think is ugly and I cannot play whatsoever because of the shape of its neck. My friend Ike calls them “meatgrinders.” My hope was that someday I wouldn’t stumble when I came to the Telecaster, and I wouldn’t be startled by the incongruity between my brain and the text. However, on that evening, hung up yet again, I thought: Maybe you should just change it? But I couldn’t. I didn’t want this particular guitar in my book because I couldn’t see myself with it, and that seemed important because Chris and I were so similar. Besides: again, it was a small detail.

Maybe this sounds like too much fuss over an object, and maybe my obstinance about changing it sounds ridiculous. But this unwillingness to revise some aspect of a story that could possibly make it stronger purely on the basis of “I don’t want to” is a big one, both in principle and practice. And, sadly, it’s not uncommon. It comes in other forms like “That’s not what I intended,” as well as, “Then it won’t be my story.” Turning a blind eye toward even a small aspect of a piece can keep a story from reaching its potential, and have the same effect on a writer. I’d been taught this, and I believed it. I revised. I revised a lot. But here I was unwilling to really consider this change, using the “I don’t want to” card.

That night, however, I stayed at my desk, determined to make a decision once and for all. Finally I asked, “Okay, why the SG?” It was a quiet question, and, though I often envisioned the scenes in my stories in my head, I definitely didn’t expect a physical response.

Then I heard, Pete Townsend.

The words came to me clearly, just not aloud. And I knew it wasn’t coming from internally, because I never thought of Pete Townsend. In fact, I couldn’t stand The Who.

"The words came to me clearly, just not aloud. And I knew it wasn’t coming from internally, because I never thought of Pete Townsend."

Then I heard the voice again say, Just listen to them again, and concentrate on the drums. You have to listen to them through Keith Moon.

I thought, Is that the name of their drummer?

Dude.

So I put on Who’s Next? and listened. I listened to the band through Keith Moon, and the experience was revelatory. Despite being in bands with drummers that people raved about, I never quite understood the intricacies and nuances. Suddenly I was hearing The Who in an entirely different way. It was like learning to read all over again.

See what I mean?

Chris got his SG.

I assumed this change would be minor. Replace one object with another. But when I changed this aspect, I then needed to rewrite a section of dialogue where Chris’s dad asks about the guitar he’s saving for. Excited about the guitar itself and that his father has asked, Chris draws a picture of it on a napkin. Only in this version the image is different, and Chris’s dad actually makes fun of it before reminding him he can’t afford it. In the previous version, he hadn’t done this, but the new image led him there, and it wrecks Chris. Then his father suddenly offers to help him out by giving him a raise and an advance so he can get the guitar, but only if he agrees to work some weekends after school starts.

I never had an experience close to this, and I realized what Chris was walking into. But I sensed this is what I’d come for, the revision. I figured, if I’m going to let Chris have what he wants, I should let his father as well. As a writer, it was surprising, exciting, and heartbreaking to watch this unfold. Then, later, Chris realizes how he was manipulated, how in that moment his dad reeled him in by asking about the guitar, then used the drawing to embarrass him, then built him back up enough to get him to agree to run the van on weekends. From this realization, he and I both got a deeper sense of his father, and Chris’s place in his father’s life.

"From this realization, he and I both got a deeper sense of his father, and Chris’s place in his father’s life."

That night I wrote a whole new ending to the story, where he redirects that cruelty on a poor family that stops to buy shrimp by convincing them to purchase much more shrimp than they need and can barely afford. Something I would have never done, but it made for a better story. More than that, it’s a cruelty Chris needs in order to survive, and he would need to use it more intentionally instead of standing aside as he did in the first story, where the Inspector shuts down the business. I understood now that Chris would need to be able to speak up in ways I couldn’t when I was his age, and even then in the drafting process, if he was going to escape intact. Sure, this was my book, but it needed to be Chris’s story.

As I continued to work on Hustle, I made this my practice, to ask Chris questions and trust his answers. I learned to shut up and listen, because that’s when the startling dialogue happened. I learned if I stepped aside, he would reveal the darker corners. I learned to see things how he saw them, unpack the situations in ways I couldn’t have. I followed him into terrifying situations where we both had a sense he was going to get wrecked, and instances where he accidentally stumbled into grace. He taught me when I let my characters go, they will let me in.