Summer 2020

2

On Scavenging, or, How to Read Like a Poet

Molly Spencer (Class of 2017)

On Scavenging, or, How to Read Like a Poet

Molly Spencer

Class of 2017

I have agreed to write a craft essay. Four weeks ago, I promised myself I’d work on it for thirty minutes a day until it was finished. I have failed to do so.

I think my failure has to do with my training as a poet. Craft essays often rely on close reading of a poem, examining the applications of craft and their effects (and sometimes their effectiveness). They are often written from a scholar’s vantage point. While I am capable of this and understand its value, I am not interested in doing it—it feels too much like picking the lock of a poem or dissecting it surgically. It goes against my training.

My training is this: for years I wrote in the dark.

This is both literal and figurative. What I mean is that for years I wrote in the dark of early morning. I was the mother of young children, first one, then two, soon three. I wrote in the dark of the pre-dawn hours—the only time I was more or less sure I wouldn’t be interrupted. And I wrote in the dark as a writer adrift, not attached to other writers, let alone an academic enterprise. I woke early to read poetry and write things that no one ever saw, writing that was informed by no class, no craft essay, no exhaustive (and, if I may, exhausting) poetry Internet, which didn’t yet exist. I woke, and read poems, and made notes in the margins:

begins w/ description, shifts to direct address, ends on image

1st stanza, the mortal; 2nd stanza, the pedestrian; 3rd stanza, the fantastical

addresses the mule but the address is masked by subject matter until stanza 4, then we remember speaker is talking to a mule

(That last note? Don’t ask.)

"I woke early to read poetry and write things that no one ever saw, writing that was informed by no class, no craft essay, no exhaustive (and, if I may, exhausting) poetry Internet, which didn’t yet exist."

I read and took notes, and then I wrote with no hope—also no despair—that my writing would ever be anything other than words in my notebook, which every morning I set aside when the children woke.

This is to say that—although I did, after many years of reading and writing in the dark, eventually take some classes, read some craft essays, attach myself to an academic enterprise at RWW—my training was as scavenger, not scholar.

My training taught me that reading like a scavenger is the way into my own work, and that is what I want to write about in this not-a-craft essay: scavenging.

Sometimes instead of scavenging, I call it generative reading, and the idea behind it is that anything you can identify and articulate in a poem you’re reading is an option for your next poem. When you read generatively you are attentive to tropes and modes of discourse and the stance or goal of the poem: is it a plea? a complaint? a meditation? an argument? You’re attentive to words and phrases that tug at something in you, images that beckon your memories, words and syntactical patterns that feel somehow familiar or interesting. You’re noticing the poet’s moves in terms of craft, moves that interest you as a poet. Where and how are lines breaking? What experience does the sound and rhythm or the poet’s approach to stanza-making deliver? The idea is not to write in imitation of, or even “after,” the poem at hand. Nor is it that your next poem is out there, fully extant and ready to be plucked from the ether. The idea is that observing and articulating a poem’s moves and asking yourself whether you’re interested in them as options for your own work can lead you to your next poem.

Molly Spencer

I’ll show you what I mean using Carl Phillips’s poem, “And If I Fall.” When I first read this poem, I felt an alertness that, after many years of experiencing it, I’ve come to recognize as a call inviting my own work into being. When I feel this alertness, I know it’s time to scavenge, so I begin.

The title itself presents options by beginning in the middle of something with a conjunction, “And”—so I ask myself: What poems of mine might begin in the middle of something? “If” is the conditional tense: What poems of mine require me to begin in the conditional? “Fall” is a verb: What verbs belong in the titles of my poems? Why? So many options from a four-word title, and there are more in the body of the poem, which begins:

There’s this cathedral in my head I keep

making from cricket song and

dying but rogue-in-spirit, still,

bamboo. Not making…

Here the scavenging reader might ask: What object, thing, or place do I have in my head, or some other part of me, that I keep making? What do I make it from? Can I write a poem under the title: “I Make the [x] In My [y] From [z]”? She might next ask: Where in my poems can I make a list that is nearly nonsensical but somehow of-a-piece (“cricket song and / dying but rogue-in-spirit, still, / bamboo”)? What are the items and parts of speech in that list? When and why in my poems should I scramble syntax? Noticing that Phillips’s next move is to have his speaker contradict himself, the generative reader might ask: What is it that I can say in a poem that I’d have to immediately take back?

The poem continues, and so does the scavenging:

…it was

everything, that cathedral. As if my body

itself cathedral. I conduct my body

with a cathedral’s steadiness, I

try to. I cathedral. In desire. In anger.

Here, the scavenging reader might ask: what noun “was everything” to me, and is there a poem in that? How might the speakers of my poems conduct their bodies? What noun can I claim as a verb, as Phillips does “cathedral”? What abstractions, like desire and anger, belong in my poems?

"Noticing that Phillips’s next move is to have his speaker contradict himself, the generative reader might ask: What is it that I can say in a poem that I’d have to immediately take back?"

These are not the only questions one might ask oneself of this (or any) poem, but they give you an idea of what I mean by reading as a scavenger. The poem continues, but I’ll leave it there and turn to another mode of scavenging.

This one is more nuts-and-bolts-y, and has to do with identifying how language functions in a poem. Helen Vendler writes about the poem as a series of utterances by the speaker. Vendler suggests that we can classify these utterances as “speech acts” that describe how each piece of language functions (and if only I’d have found Vendler’s book Poems, Poets, Poetry twenty years ago, I’d have saved myself fifteen years of learning this on my own). Here’s a partial list of speech acts you might find in a poem: the declarative (a statement), the imperative (a command), the interrogative (a question), description, narration, exclamation, rebuttal, contradiction, dialogue, reflection, direct address, exposition. The idea is that when we notice how language functions, we can map a poem’s structure and use it in our own work.

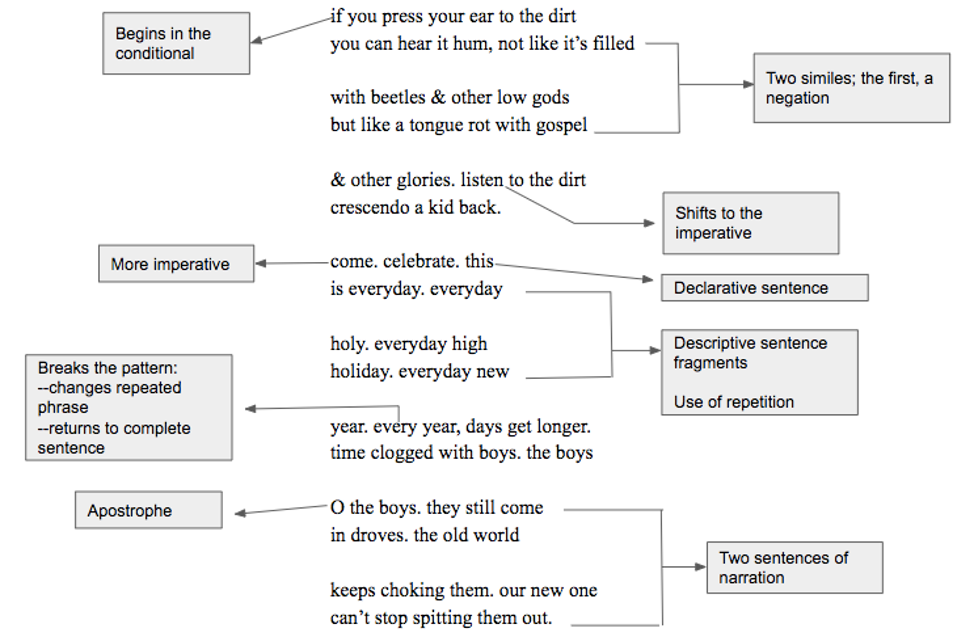

Again, it’s easier to understand this if you see it in action, so here’s a section of Danez Smith’s “summer, somewhere” that I’ve mapped:

The map of this excerpt in my notebook might look like this:

Begin in the conditional

Two similes, one a negation

Shift to the imperative

Declarative sentence

Descriptive sentence fragments with repetition

Change repeated phrase; return to complete sentences

Apostrophe

Two sentences of narration

The next step is to draft into this structure. Of course, there’s no obligation to stick to the map once you’re in the territory of your own work. The idea is to get you into that territory.

There are other ways of scavenging—quick and easy things to do as you read. One is to make lists of words the poet uses that interest you. Another is to write down lines, or phrases, or even an entire poem, that interests you. There are pages and pages in my writing notebooks that exist only as lists of words and phrases from my reading. It’s not unusual for the act of making lists to bring my own words to the page, and I often find myself interrupting my list-making to draft a poem. (Pro tip: the lists of words are also valuable during revision.)

"Another way to read as a scavenger is to read a lot, and widely, embracing the mysterious way that reading improves our writing as if by proximity or osmosis."

Another way to read as a scavenger is to read a lot, and widely, embracing the mysterious way that reading improves our writing as if by proximity or osmosis. My (possibly unpopular) opinion is that your first obligation as a reading poet is to your own work: you should read the poems that bring you to the alertness that precedes your own writing. But I would also urge you to understand that the dominant culture has long determined what gets published and read, and to read extensively and outside of your own taste and style. Read outside the mainstream. Read poets whose work has traditionally been undervalued because of racism and other forms of bias. Read things you don’t really even enjoy. You needn’t read every poem or every book of poems generatively, but you’ll enrich your own creative life and the conversation amongst poets across time and space by reading as a participant of it.

To read as a scavenger, you’ll have to read in the dark, without the locksmith’s tools or the surgeon’s headlamp. But if you nose around in a poem, leaving aside what doesn’t interest you and picking up what does, I believe you’ll write authentic poems with the materials of your lived experience and language—the poems only you can write.

Phillips, Carl. “And If I Fall,” Star Map with Action Figures, Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019, p. 11.

Smith, Danez. “summer, somewhere,” Don’t Call Us Dead, Graywolf, 2017, pp. 3-22.

Vendler, Helen. Poems, Poets, Poetry: An Introduction and Anthology, 2nd Edition. Bedford, St. Martins, 2002.

Molly Spencer is a poet, critic, and editor. Her debut collection, If the House won the 2019 Brittingham Prize judged by Carl Phillips. A second collection, Hinge, was co-winner of the 2019 Crab Orchard Open Competition judged by Allison Joseph, and is forthcoming in October 2020. Molly’s recent poetry has appeared in Blackbird, FIELD, The Georgia Review, Gettysburg Review, New England Review, Ploughshares, and Prairie Schooner. Her critical writing has appeared at Colorado Review, The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review online, The Writer's Chronicle, and The Rumpus, where she is a senior poetry editor. Her poems have won a Lucile Medwick Award from the Poetry Society of America, a Glenna Luschei Award from Prairie Schooner, and a Writers@Work Fellowship Award. She holds an MFA from the Rainier Writing Workshop and an MPA from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, and teaches writing at the University of Michigan's Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.