Spring 2020

2

Some Thoughts on a Practice and Poetics of Philia

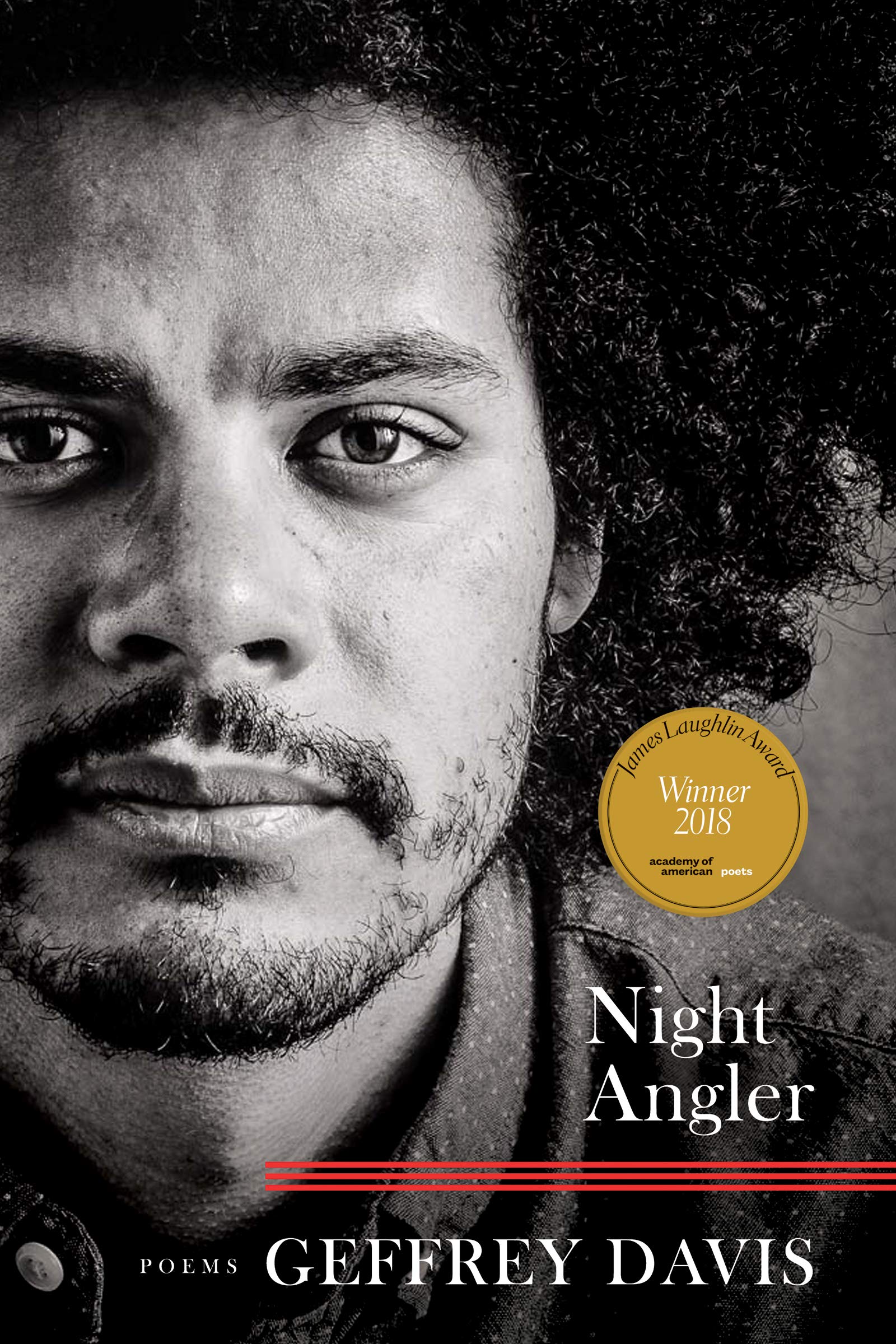

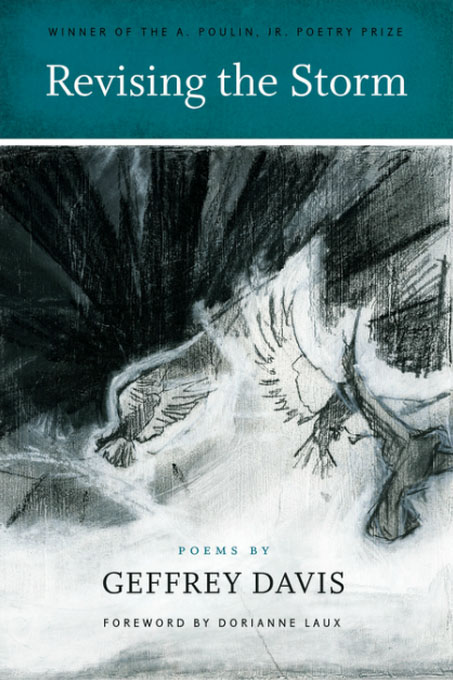

Geffrey Davis, Faculty

Some Thoughts on a Poetics & Practice of Philia

Geffrey Davis

Faculty

I.

Maybe it’s the sense that I’ve seemingly entered an ongoing, tender season of saying mortal goodbyes to literary voices I’ve loved, but I keep thinking about the proximity between song and survival. And it’s making me sentimental.

The other day, all weepy, I tried telling another room of writers how I loved the meaning of their living voices, how that love had me hoping and assuming that I’d hear their voices together again, maybe even in future shared rooms. And I tried confessing my ever-growing guilt over each artist hero we have lost early, how maybe some of them, if we blessed harder or cared more clearly or asked only for more time with their hands, maybe some of them would still be here, blessing us with their light.

As I spoke, I felt the sadness that was already there building against my pressure to clarify the kind of love I wanted for them, but I kept at it. I said (and was saying to myself) we don’t get to sing a song that we don’t survive, not without risking teaching those that we leave behind how to gamble with their own not being here. I promised to never love any metaphor or image or sound they would make more than the breath they needed to create poems and narratives. I asked them, more and more weepy, yes, to search out the ineffable edges of metaphor and story, but then to come back to me—to let me always hear them making their ways back.

"I promised to never love any metaphor or image or sound they would make more than the breath they needed to create poems and narratives."

II.

As a teacher who believes in a healthy amount of irreverence, I’ve been known to allow some time for class participants to engage and question the shortcomings of the very structure we’re in, if only to reimagine the kind of autonomy and agency that an institutional setting can inadvertently limit. In this spirit, I recently spent a brief portion of an afternoon with seven graduate writers pointing out the challenge of us reading an assigned collection of poems per week, a pace that I had decided for them, and was myself committed to keeping. I was mainly referring to time and energy; they each have other responsibilities—to jobs, to their own teaching, to families, and to myriad other aspects of lives being lived. I admitted that poetry demands a certain level of intensified attention and/or an intense submission to another’s subjectivity, and that the pace of a book per week maybe didn’t really allow for much interruption to one’s focus. For example, I told them, after years of silence, just that morning I was surprised by a voicemail from my father. He sounded lonelier than ever through the line. And since I hadn’t yet prepared for that day’s meeting, I had to read our collection while the possibility of a return-call contended with my attention, piercing the margins of my awareness over and over again. It was brutal.

But my contract with them pushed me forward, as did the splendor and counter-struggle of Carolina Ebeid’s collection, You Ask Me to Talk about the Interior. Waves of what I interpreted as recognition spread through the room, parallel but distinct worlds of effort they each had overcome in the name of being together through poetry. And rather than diminish our purchase on discussing the work, the conversation that ensued felt leavened by urgency and friendship, in sharper honor of what our days had collectively been up against, and I left with this line from Ebeid’s collection ringing in my ear: “You have learned us worship,/ teach us to remain in love.”

Then I called my father back.

III.

In Madness, Rack, and Honey, Mary Ruefle writes, “Cries and whispers. A bang or a whimper. Whatever the case, if we want to be heard, we must raise our voice, or lower it.” It’s one of those lines that resonated immediately, and so I added it by hand to the commonplace notebook that I often carry with me. Indeed, this quote has been welcomed company for several years now—a warm reminder that, especially when working through some of the loudest griefs in my head, so much of my safest speech has required softening.

And then, during the launch of her wonderful book Ozark Crows, my poet friend Carolyn Guinzio played a slowed down audio recording of an American crow caw. It was a poem. At that speed, the bird’s call sounded like “hey” and had what you might describe as human syllables; it sounded closer to what my ear understood as the prayer for recognition inside all song. Or maybe, I could read my own longing according to the sudden otherness of that bird’s song. Either way, what I recognized in the call moved me—no, it changed me. I’ve probably loved and noticed crows for most of my life, but I got to know more of my love by hearing the (invented) margins of one crow’s voice, shared by a friend.

"And then, during the launch of her wonderful book Ozark Crows, my poet friend Carolyn Guinzio played a slowed down audio recording of an American crow caw. It was a poem."

And then some virtual friends inadvertently introduced me to a series of photographs by the artist Adrian Borda, taken from the lit-inside of musical instruments. The first photo I sat with had a cello as its subject. The shift in perspective and the way he used light to illuminate the interior, again, changed me. In photography, the characteristics of light include direction. Traditionally, flat light refers to light facing directly at the front of a subject, backlight refers to light coming from behind a subject, and sidelight refers to light coming directly from any side of a subject. But what do you call light that’s been aimed to shape the interior? I want to call this picture a poem. Borda’s work also invited me to consider once again how each instrument of art is also its own subject.

What I’m trying to say is, I appreciate that friendship, like poetry, can facilitate how we forget and remember the changing margins of our voice, how those (new) margins both obscure and reveal us to each other. And so, through friendship and poetry, the next chapters of searching and believing in people (even those who need to yell) get renewed, offering occasions for hearing the possibility of something kinder, less alone, more connected.