Spring 2019

2

A Marriage of Words

Wendy Willis & David Biespiel

A Marriage of Words

Wendy Willis

Class of 2013

David Biespiel

RWW Faculty

Wendy

It is impossible to write about the blessings and pitfalls of literary love affairs without first paying homage to one of America’s great writerly couples—Judith Kitchen and Stan Rubin. It was an inspiring and fearsome thing to behold, the force that was—and in many ways still is—Judith and Stan. They were brilliant and brash and opinionated. They talked over each other. Constantly. They laughed at each other’s jokes. They transferred information one to another through the raise of an eyebrow, the tilt of a chin. Each believed the other was the most extraordinary person he or she had ever met. Each encouraged the other to be more Stan, to be more Judith.

Despite our disagreements on things like, say, Frito pies, David and I are pallid by comparison. Truth is, the kind of advice I want to offer runs toward the pragmatic. I’m thinking: Always stash an extra bag of coffee in the back of the pantry and don’t skimp on heat, even if it means lighting a fire in the backyard. No one writes well or loves well if they are sleepy and cold. Maintain a shared calendar so you don’t get annoyed about overlapping events. Walk the dogs together. Save your catty literary gossip for each other; don’t drag anyone else into it.

But I’m sure no one really wants my relationship advice, so I will tell you this:

The most extraordinary gift of being in a marriage rooted in literature, in ideas, in words, oddly, is the silence. On the rare days when we are at home alone together and the kids are away, David and I can sit side by side in front of the living room fireplace for hours and not say a word. Sure, every once in a great while, we might ask, Do you need a cup of coffee? But that’s about it. Or we go to separate rooms and peck away at our his-and-her MacBooks and never feel anything but joy and gratitude for the quiet that settles over the house. It is magical, really, trying to make sense of the next stanza, the next paragraph, hearing only the soft click of the keyboard from the other room and the dogs sighing in their sleep on the couch.

"The most extraordinary gift of being in a marriage rooted in literature, in ideas, in words, oddly, is the silence."

In the evening, we come together. Don’t get me wrong—it’s not candlelight and bay scallops. It’s a crazy juggling act of work-related events, teaching schedules, and kids’ performances. And sometimes—more often than I’d like to admit—dinner is at 10 p.m. Most of the time I cook while David sits at the counter or in the rocking chair in the middle of the kitchen, and we swap stories of the day. Sometimes we talk about a dilemma in one of our poems or essays, sometimes we talk about Violet’s physics homework, sometimes we talk about the stove that seems to be on its last legs, and sometimes we talk about the presidential primary. But it’s all of a piece. We’re trying to live as well as we can inside of a busy family inside of an old and drafty house. We’re trying to make something in the midst of everything. And we can’t wait to see what the other one does next.

David

Some of the earliest surviving manuscripts by the late British poet Ted Hughes date to the beginning of the 1960s. That’s when Hughes was married to Sylvia Plath, and the young couple were living in London, frequently writing together at a small kitchen table, with something like a cardboard box at their feet overstuffed with discarded manuscripts.

Hughes’s habit was to compose poems on any scrap paper at hand. He wrote on envelopes, the backs of letters, wrapping paper the fish came in—and on the back of his own and Plath’s own discarded manuscripts in that London kitchen. Plath, too, wrote new poems on the backs of Hughes’s discarded manuscripts—according to Diane Middlebrook’s biography, Her Husband, in which she describes how the two poets shared and reinvented each other’s images and ideas, how their work often took the form of a kind of call-and-response.

Early on in our time together, Wendy and I invited the other to pilfer phrases we liked from each other’s drafts of poems, even finished poems, and insert them without attribution into our own poems. It was the beginning of a marriage of words.

"Early on in our time together, Wendy and I invited the other to pilfer phrases we liked from each other’s drafts of poems, even finished poems, and insert them without attribution into our own poems. "

Perhaps it was meant to simulate the call-and-response of Hughes and Plath, but mostly it was to put into the field our intertwined imaginative lives as they revealed themselves through our own poems. We didn’t write poems together, we only revised each other’s poems lightly, and we never would tell the other what or what not to write—but if I favored a fructifying phrase in one of Wendy’s poems, or if she favored something out of one of mine, we plucked it and dropped it into whatever we were writing. The close readers among you will find the overlaps in our poems.

Of course, I never expect anything like the tragic fate of Hughes’s and Plath’s marriage to happen to us! Plath committed suicide when the couple was separated in 1966. We don’t literally write on the back pages of each other’s manuscripts—we don’t even own a printer. But we do write, for better or for worse, sometimes more often and sometimes less often, in response to what the other is making. Or making from. Or responding to.

We write, not on, but from the back of each other’s interior experiences, I guess is what I mean. Not that we sit around all day cinematically composing poetry to each other in front of an open fire—Wendy in a Victorian collar, me with an ascot and pipe. But we inhabit the playgrounds of each other’s interior lives. The outcome of that play—that puttering and loitering and mucking around inside the interior life, the dream life, the imaginative life—reveals itself over cups of coffee in the morning or at dinner parties with friends or in the discarded stuff of living we share with each other.

Discarded? Is that really what I mean? Forsaken? Is that what I mean? Repudiated? Thrown overboard? Purged? Jilted? No, not exactly. More like offered. More like put forth, tendered, allowed, prompted. What I mean is, we seek out a kind of listening to the other, pull that language into our own writing, and then, through mixing that language into one’s own new writing, say something back.

As with so much in a writing life, alertness is everything.

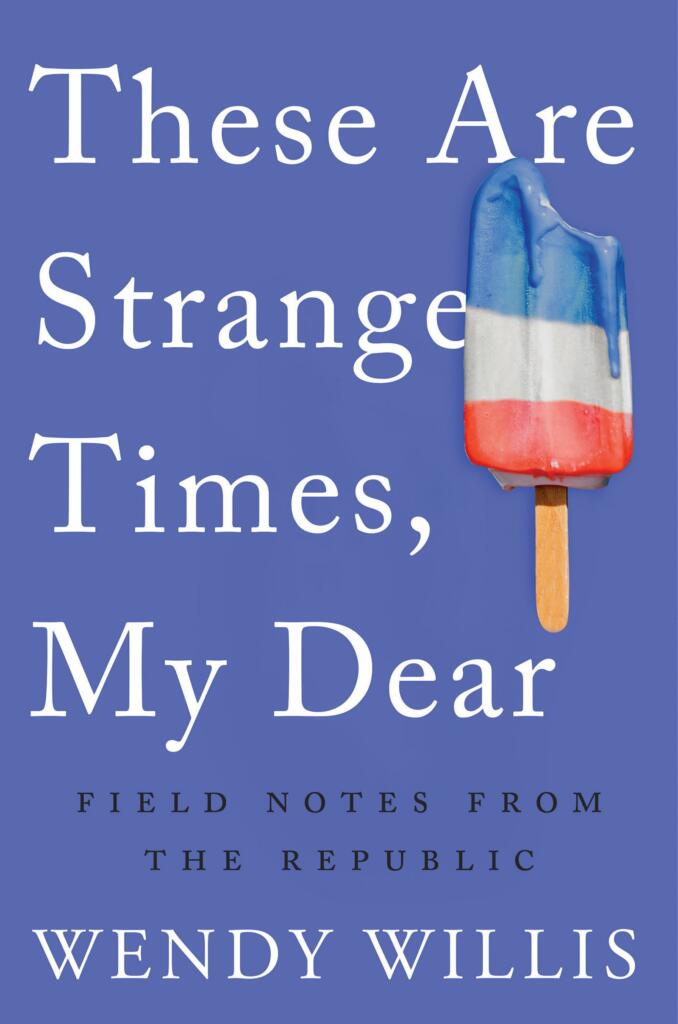

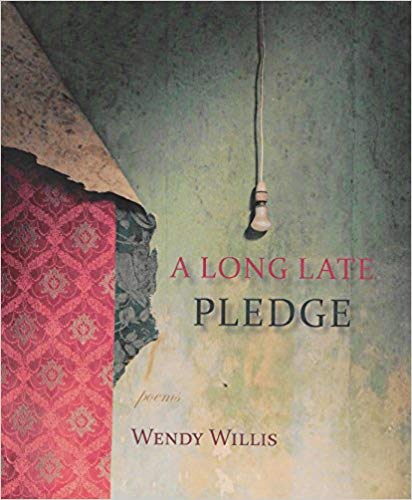

Wendy Willis is a 2013 graduate of the Rainier Writing Workshop. Winner of the Dorothy Brunsman Poetry Prize, she has published two books of poems. Her last book of poems, A Long Late Pledge, is a finalist for the 2019 Oregon Book Award. Her book of essays,These are Strange Times, My Dear, was released in February. She lives in a drafty, 100-year-old house in Portland with her husband, David Biespiel, and their family.

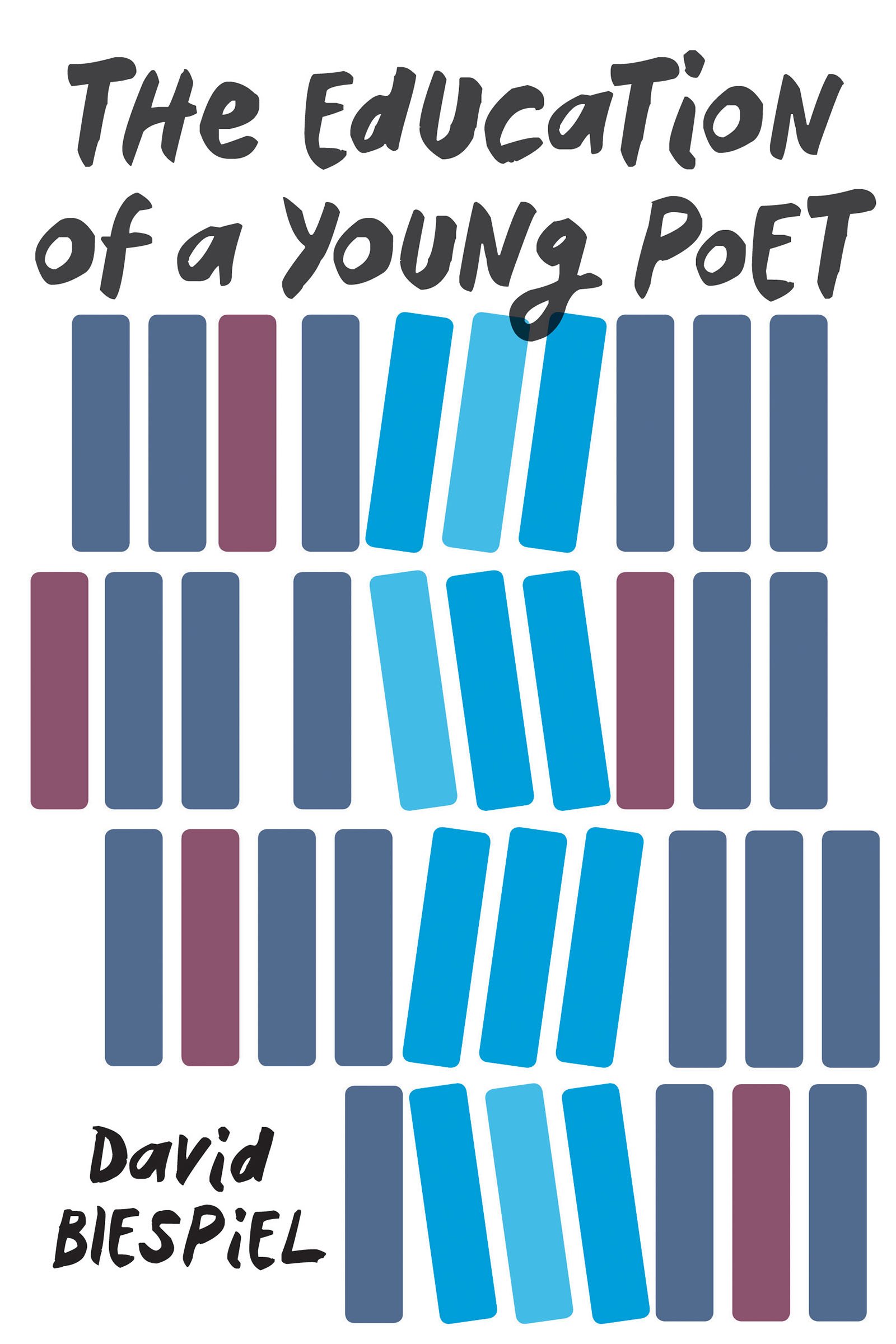

David Biespiel is the author of eleven books, most recently Republic Cafe (poems) and The Education of a Young Poet (memoir). He’s a contributing writer to American Poetry Review, Poetry, The Rumpus, New Republic, The New York Times, and Slate. Awards for his writing include an NEA Fellowship, a Lannan Fellowship, and two Oregon Book Awards; he was recently a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Balakian Award. He lives in a shambling, 100-year-old house in southeast Portland with his wife, Wendy Willis, and their family.