A Conversation with Tracy Daugherty

It all goes back to writing what, or who, you want to know.

________________________ —Tracy Daugherty

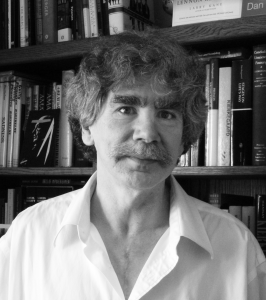

Magic happened on the last day of July 2016: Tracy Daugherty, reading from a work in progress, enthralled the audience in the Scandinavian Cultural Center at Pacific Lutheran University. Daugherty’s as-yet untitled biography of Billy Lee Brammer is the perfect intersection of history, personality, region, and pop culture. It’s a genre Daugherty calls cultural biography, and he loves to write it.

Billy Lee Brammer—novelist, king of backroom politics in Dallas, counterculture figure (as well as father of RWW alumna Sidney Brammer)—seems to have been in all the right places at all the right times in the 1960s. Daugherty’s book focuses on Brammer’s shadowy presence in Dallas leading up to the Kennedy assassination, allowing Daugherty to exploit the familiar details of the events of November 1963 and combine them with an intimate description of the down-at-heels neighborhoods of a Dallas soaked in sordid, grotesque, and sometimes comic specifics. After an hour of breathing in the atmosphere of the hardscrabble backrooms of Dallas in 1963, it was hard to relocate oneself in the 21st century.

This is what Daugherty does: draws you into a situation that you think you know, and then spins a tale that immerses you in details you expect from a novel, but with the episodic urgency of a short story, all the while unraveling the stories of the little known but pivotal characters. At the end of the reading, Daugherty, this year’s Judith Kitchen Visiting Writer, answered questions from writer and Rainier Writing Workshop faculty member Dinah Lenney and a few notable Texans in the audience. He covered subjects from his research process to the ethical dilemmas inherent in writing the biography of the father of a former student and colleague.

Author of three literary biographies, four novels, four short story collections, numerous articles published in journals from the New Yorker to TriQuarterly, as well as a book of personal essays, Daugherty found early inspiration in the political speeches made by his grandfather, an Oklahoma politician, also named Tracy Daugherty. “Seeing my name on posters and hearing his speeches, I fell in love with the power of words,” he says. He grew up with an ear toward the influence of the political and a passion for place and pop culture. Born and raised in Midland, Texas, he studied with Donald Barthelme, who, he says, gave him the best, albeit unorthodox, advice for unleashing the imagination. He shares this advice, as well as what he considers the worst advice a writing student can get from a teacher. Read on for a fascinating and generous conversation on early influences and how we become artists.

***

Colleen Rain: One of your early influences was your grandfather’s political speeches. How did you bridge the gap between written and spoken word in your own craft?

Tracy Daugherty: My grandfather was an old-time politician and a great orator. I would hear him give these speeches and then later, I realized he was writing them out. Most of his speeches were stories, so they were the first exposure I had to someone writing stories out and then delivering them. He was a great tale-teller and the connection between the written and spoken word was impressed on me at a pretty early age. I owe to my grandfather an awareness of audience and I think it really helps to write with an audience in mind. You have to be clear; you have to keep the pacing up, so nobody gets bored. It is like delivering a speech on the page.

CR: It sounds like a clinic on good poetry. How did you avoid poetry with all of that early influence?

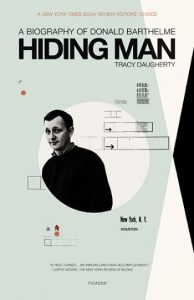

TD: I didn’t! I wanted to be a poet. When I first went to an MFA program I applied as a poet and started writing poetry. Donald Barthelme, the subject of my first biography as well as a teacher of mine at the University of Houston, sidetracked me back into prose. He saw some of my poetry and he thought I was more of a prose writer. I don’t remember any of his comments, except, “You should be in my class.” So I enrolled in his class and took all of his advice from then on.

CR: I loved reading your biography of Barthelme, Hiding Man. As his biographer, can you talk about your experience of writing this after being a pupil of his? Is there anything you learned about the art of being an artist?

TD: One of the first important lessons for me was when I was writing about him. His writing was so avant-garde and strange. I would read him and not understand a word of what he’d written, and I’d think this guy must be really weird, and that to be an artist like that he must be out there on the edge somewhere with some wild lifestyle. But what was wonderful, not only meeting him but digging into his career, was to realize he was a very pragmatic, disciplined guy. He began as a newspaper reporter, had a career and raised a family. It was a real revelation to me: that this amazing art came from someone who stayed at his desk all day, and it was just hard work. It’s not about some magical adventure you’re on; art doesn’t come from the ether, and it’s all hard work. The trick was he made it look easy, but it was all hard work. That turned out to be true about Joseph Heller and it turned out to be true about Joan Didion. These are all hard-working people. It isn’t glamorous but it’s the most important lesson I’ve learned.

TD: One of the first important lessons for me was when I was writing about him. His writing was so avant-garde and strange. I would read him and not understand a word of what he’d written, and I’d think this guy must be really weird, and that to be an artist like that he must be out there on the edge somewhere with some wild lifestyle. But what was wonderful, not only meeting him but digging into his career, was to realize he was a very pragmatic, disciplined guy. He began as a newspaper reporter, had a career and raised a family. It was a real revelation to me: that this amazing art came from someone who stayed at his desk all day, and it was just hard work. It’s not about some magical adventure you’re on; art doesn’t come from the ether, and it’s all hard work. The trick was he made it look easy, but it was all hard work. That turned out to be true about Joseph Heller and it turned out to be true about Joan Didion. These are all hard-working people. It isn’t glamorous but it’s the most important lesson I’ve learned.

CR: I’m grateful to hear you say that. It’s so encouraging! I think of art and writing as an avocation, not a lifestyle choice. Berets and half-moustaches, optional!

TD: I’m glad you used that word “avocation,” because art, and writing anything that is noncommercial, is a calling. It’s more than just a job, and it means you devote your life to it, but that doesn’t mean you don’t have to put in the hard hours. It’s about persistence, too. We look at people like Heller, Didion, Barthelme, from the point of view of their success and we think they must have had some kind of luck or advantage or something we lack, but it’s not true. They had setbacks and failures. You really have to just accept the rejections you get and go on.

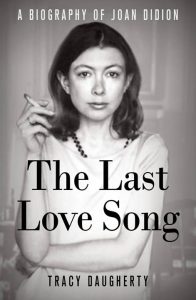

CR: Reading The Last Love Song, I noticed a real shift in your attitude toward Didion: you went from being suspicious of her self-constructed persona as an artist, to a validation and even admiration of that persona. It was interesting to watch the transition you made, as if you discovered a few different Joan Didions in the course of writing. You also mentioned in your Q and A with Dinah Lenney that you had your master class read six different biographies of Willa Cather and found six different women. Can you talk about how the process of biography helps you find ways to construct your own stories?

TD: That is something I’m trying to come to terms with, but I think it’s absolutely true that even a biographer is writing autobiography to some extent. I think it begins when you pick your subjects. By choosing to write about Joan Didion I’m revealing something about myself, and my interest in her goes way back. I’m drawn to her because she writes about politics and culture, and in choosing to write about her, I’m telling some parts of my story. I chose her because her prose rhythm matches my prose rhythm; it’s a kind of music that matches the music in my head. A biographer has to be careful not to let his or her own obsessions influence the story of the subject, but it’s part of my own story in telling hers. The biographies I’ve written are cultural histories as much as the stories of an individual life, because that’s really what I’m interested in: how the culture around us shapes our sensibilities. Didion was the perfect subject for this.

TD: That is something I’m trying to come to terms with, but I think it’s absolutely true that even a biographer is writing autobiography to some extent. I think it begins when you pick your subjects. By choosing to write about Joan Didion I’m revealing something about myself, and my interest in her goes way back. I’m drawn to her because she writes about politics and culture, and in choosing to write about her, I’m telling some parts of my story. I chose her because her prose rhythm matches my prose rhythm; it’s a kind of music that matches the music in my head. A biographer has to be careful not to let his or her own obsessions influence the story of the subject, but it’s part of my own story in telling hers. The biographies I’ve written are cultural histories as much as the stories of an individual life, because that’s really what I’m interested in: how the culture around us shapes our sensibilities. Didion was the perfect subject for this.

CR: You said something in the Q and A with Dinah that really spoke to me: that people read biography in order to find out how to do the things they want to do. I know biographies were instrumental for me to find a path to writing when I had no idea how one went about being a writer. How do you think this works for artists and writers?

TD: I didn’t read biographies when I was young, though I wish I had. I came to this understanding about biographies much later, when I was writing them. Like you, I didn’t know where to turn for advice to be a writer or even know what a professional writer was. My first exposure to crafted language was my grandfather’s political speeches. I would see him write a speech and then deliver it and that made me think there is a lot of power in language. Then I began to look at newspapers and realized it wasn’t just the daily news—that’s a form of writing, so people must be doing it—those were the things that I thought about when I thought about public language. It was only much later when I began to research and write biographies that I began to realize how much wonderful information is in them, about how a person turns to art when they don’t know how to do it, how they first learn, how they find teachers and mentors. That’s when I realized this is a track so many people take: turn to biography as a sort of how-to book or a manual. I think it’s a great source.

CR: Does the biography work spill into the fiction and short stories you write?

TD: Fundamentally, I don’t think there is that much difference between writing fiction and nonfiction. People often ask me this, but aside from the fidelity you have to have to facts in nonfiction, I don’t think there is that much difference at all. It’s all a narrative, it’s all telling a story, it’s all deciding what to leave in and what to leave out. I don’t think there is a very great difference at all.

CR: Is that how you keep more than one project or genre going at the same time?

TD: It’s useful to keep more than one project going at once, to step away and then come back. I don’t think of myself as a short-story writer, but working on novels, which never seem to end, I turned to short stories as a kind of break and found out I enjoyed writing them. The going back and forth is a lot of work, but I like staying busy and I think the variety of writing I do as well as the research keeps me going. I’m not monotonously boring into one thing. For my first novel, I had to research the life of a cartographer, and I found the more I researched, the more my character took shape. I learned pretty early on that research was a wonderful stimulant. In fact, when I was working on that novel, I was a student of Barthelme’s and he was reading it. One night he went to a party and met some hot-shot petroleum geologist, and he came to me and said, “I met your character last night, you should go talk to him.” I did, so from the beginning, research has been an important part of writing.

I don’t think this gets stressed enough in writing programs. There’s so much emphasis on following your voice, using your imagination and creativity, which is important, but not enough on research. Didion is a great model for that. You know there’s that old cliché, write what you know, but I would define what you know as what you get interested in, what turns you on. Define what you know broadly. It doesn’t just mean what you’ve experienced.

CR: Can you offer us a different paradigm?

TD: That brings us back to biography as a tool. My variation of that would be, write what you want to know or want to learn about. It’s the reason I write biography, because I want to know why or how Barthelme or Didion did it.

CR: What’s the best advice about writing you’ve ever gotten?

TD: Barthelme assigned me a poem by John Ashbery which was very abstract, and then told me to go home, read it, don’t sleep all night long, drink a bottle of wine, and then write seven pages and imitate it. He called me in the middle of the night and said “How’s it going?” That was the best assignment I ever had as a student! I’ve never given the same assignment to any student, for obvious reasons, but the lesson I took from it is you have to let go of the control a little bit—you have to sit there and do the work, but you also have to let the mind wander free. You have to loosen up, and I think that my teaching is geared toward helping students loosen up. So many younger writers start with some goal in mind, some message—and my teaching is designed to say, “Don’t start with anything, let the imagination go. Loosen up.”

CR: And the worst?

TD: Let’s go back to write what you know. It’s so limiting. I understand the intent: you have to know what you’re talking about. Your own obsessions and your own experiences are crucial, of course, but that whole notion you can only write what you’ve experienced is a tiny little box we don’t have to cram ourselves into. It’s not politically correct, and there are some who say you shouldn’t write as a woman if you’re a man or as an African-American if you’re white, and I understand the politics and delicacy of this. But I don’t buy it; you have to write your way into other lives. I think the advice that limits you is the advice that says write only what you know, stay true to your own experience. I think that’s bad advice.

CR: So could we say that you think that writing across race and gender is a way to stimulate or learn empathy?

TD: Yes. I’m very sympathetic with the reasons people employ to say it shouldn’t be done. It’s complicated, and I’m not advocating appropriating the voices of people who are different from you. “Do you have the right to do that?” is a very important question to ask if you’re going down that road. It all goes back to writing what, or who, you want to know.

_

_